Embracing Empiricism — From Randomness to Reason

Cultivating a culture of critical thinking for effective and impactful outcomes

published 16 April 2025

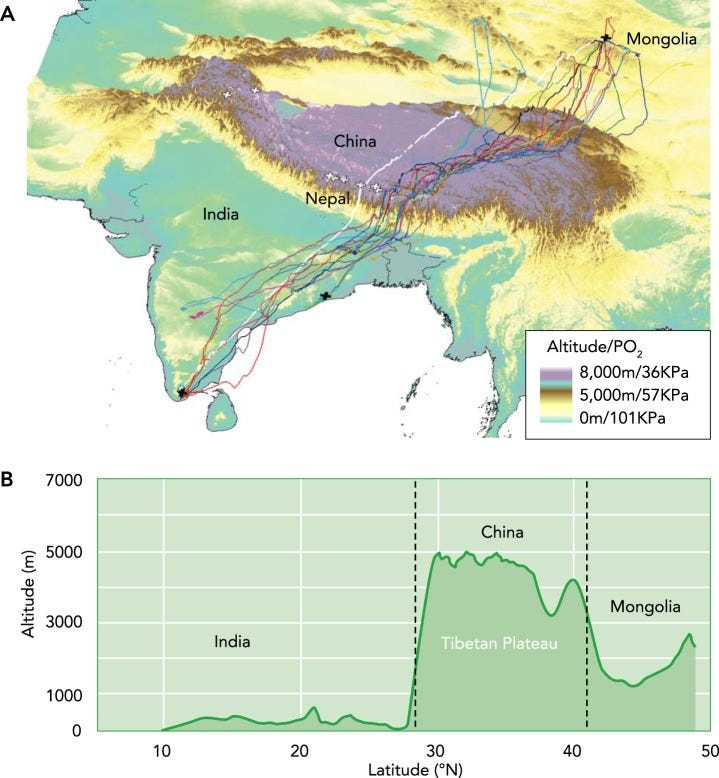

There is a species of goose in Asia, the Bar-headed goose, that flies over the Himalayas twice a year, migrating between southern India and mountain lakes in the north, as far as Mongolia. At altitudes where I wouldn’t be able to run for 1 minute without having a heart attack, these birds manage to flap away for hours on end, sustaining the greatest rates of climbing flight ever recorded for a bird.

An awesome feat. My first reaction to this fact is wonder. But I am also touched by a sense of tragedy.

You see, the Bar-headed Goose evolved these marvellous abilities because millions of years ago the Indian subcontinent came crashing into Asia. This collision, which still continues today, crushed up the Earth to create the Himalayas. As the mountains slowly grew, the bar-headed goose gradually evolved its flying abilities to keep up with the growing mountains. Here is the wonder.

The tragedy is that the Himalayas are still growing. There will eventually come a moment when it will just not be possible physiologically for these birds to fly any higher. At that moment this amazing story will end.

Evolution

Evolution is senseless, without direction, a random accumulation of characteristics. While most of us have a pretty romanticised view of evolution, in awe of all the variety of life it has created, the truth is that this is a cruel and harsh process, and terribly wasteful.

With evolution, it is all about chance. Improvements come from mutations — random changes to DNA. And yes, this should indeed cause you to raise your eyebrows, because as we all know mutations are not a good thing. Cancer is an example of mutation, cells changed in some way so that they don’t function correctly anymore.

Calling evolutionary variation improvements is in fact quite ridiculous. Aberrations might be better. Or accidents. The bottom line is that the odds of a mutation being beneficial are vanishingly small.

Evolution is a bit like that mythical room full of chimpanzees that randomly pound on keyboards and will eventually manage to write a Shakespearean sonnet. Eventually. After millions of years and all while creating infinite amounts of useless junk.

Oh, and after the breathtaking sheer luck of getting a mutation that will not actually kill you and give you some advantage instead, you are not there yet. That change must still survive environmental hazards, predators, disasters, random things falling on your head, and the fickleness of mating success.

Darwin talked about the survival of the fittest, but fitness is only part of the equation. A very small part. Randomness is the rest.

It is truly a wonder that evolution works at all. And not surprising at all that it takes so desperately long to get anywhere.

Empiricism

Empiricism on the other hand is about getting rid of the luck factor. No playing dice here, but instead clear direction and deliberate precision in selecting improvements and making sure they persist.

Where evolution is slow, unguided, and shaped by randomness, empiricism is an intellectual endeavour. It is evolution under strict controls, fast, guided by purpose, and shaped by insight and critical thought.

We use our intellect to determine and adopt improvements towards fulfilling our goals. Empiricism is about coming up with solutions based on a deep understanding of the problem. It is about coming up with something that makes sense, something you are thoroughly convinced might work.

The effect is significant.

While still relying on mutations, farmers have used an empirical approach to improve crops and domestic animals for thousands of years, giving us the huge variety we now take for granted. To give you an idea of how extensive this is, there are over 3,000 varieties of rice, all stemming from one original wild species. The original Aurochs have spawned over 1,000 breeds of cattle. We have more than 300 breeds of chicken. Perhaps the winner is wheat, with the US seed vault containing 62,000 different varieties, again all stemming from one wild species!

Empiricism has changed our diets, environment and our civilizations.

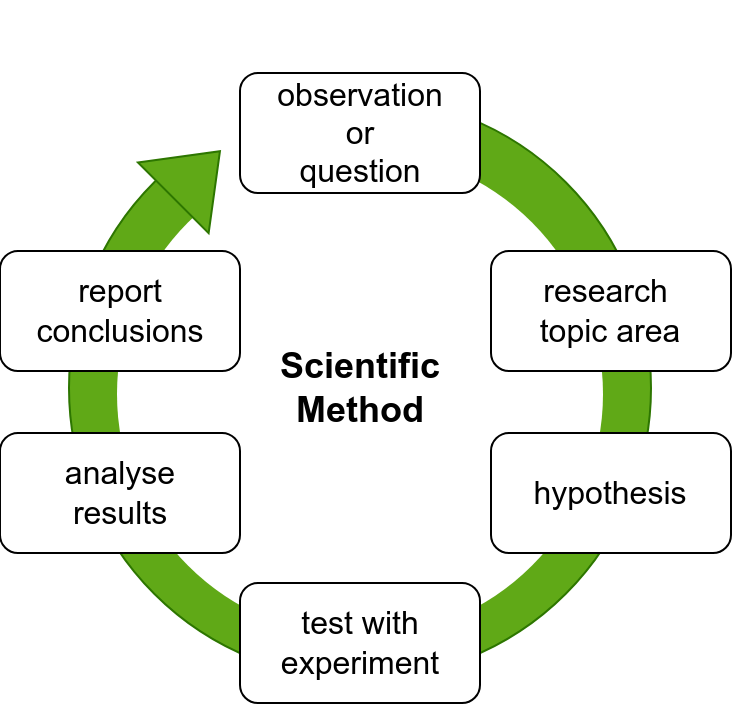

Science takes it a step further. Formalising empiricism to create a strict and rigorous process called the Scientific Method, it has done away with the reliance on mutations, instead creating variation based on a fundamental understanding of the subject. This has led to an amazing level of progress. Just think about it, in 400 years we have completely changed the world into something my grandparents woudl struggle to understand. It took us 400 years to learn how to fly, while nature required millions of years.

Essential to the Scientific Method is the focus on thinking deeply about the problem at hand. Experimentation only starts after you have understood the problem so completely you are prepared to propose a rational and solid solution (the hypothesis). Only then do you experiment, and only to validate the solution.

This is taken so seriously that in scientific circles that it is a big no-no to do just any odd experiment to see where it will take you. Without a solid, convincing and well-thought-out hypothesis, you will be ridiculed.

The reason for this is simple. Without a hypothesis to validate an idea, you are just shooting in the dark and fishing for patterns, and that just opens up a huge can of worms — the realm of your very human biases.

Empiricism and Agility

Agility is in essence a new step in our evolution of empiricism. In this case, the innovation is about having all employees join in, turning the whole organisation into a Learning Organisation. All frameworks focus on achieving this by concentrating on two things:

involvement of the whole workforce, by creating autonomy and ownership and transferring responsibility to them,

feedback loops adapted to the way of work, but with the same foundation as the Scientific Method.

For example, looking at the most popular Agile framework, Scrum:

“The fundamental unit of Scrum is a small team of people, a Scrum Team. … a cohesive unit of professionals ... self-managing, meaning they internally decide who does what, when, and how.”

“Scrum is founded on empiricism and lean thinking. Empiricism asserts that knowledge comes from experience and making decisions based on what is observed.”

— Scrum Guide —

It is this embracing of empiricism at all levels of the organisation that makes Agile so effective… when done properly.

And here in lies the crux, that empiricism is hard, really hard. It takes discipline and rigour. It is not for nothing that scientists spend at least 6 years studying at university and have to defend a thesis before they may formally call themselves scientists.

In contrast, in an Agile approach empiricism is taught in an indirect and unformalised way. Empiricism is presented theoretically but with little explanation of how to put it into practice. The idea seems to be that by focusing on the Agile framework, people will learn by rote, much like the Karate Kid — wax on, wax off.

But empiricism is nothing like learning karate moves.

The results are not surprising. Agile transformations successfully take the step of involving employees. But they fail because those same employees are not able to adopt empiricism effectively.

People mostly end up going through the motions in an ineffective parody of empiricism. And if practised at all, empiricism is relegated to simply trying stuff out to learn from the results. Completely ignoring the most essential part — the thinking part. Wax on, wax off.

This is a terrible state of affairs.

While it may not be as completely accidental as evolution is, it does entail a similarly dramatic amount of waste. Witness the following examples:

solutions brought in without an understanding of what problem they solve,

initiatives without measurable goals,

metrics that do not measure anything significant,

unclosed feedback loops, where learning and adaptation are forgotten.

Conclusion

Agility is only the latest step in our relationship with empiricism, a relationship deeply tied to the way we progress as a species. This progress is not constant and has its ups and downs. The Agile Manifesto was a big step up, having a huge impact on how organisations are run. The current “Death of Agile” seems to forebode a downturn. The promise of the Agile Manifesto seems to have been abandoned and no one knows what will come next.

This presents an opportunity. If Agile is to survive its current identity crisis, we need to return to its roots in empiricism — not as a buzzword, but as a disciplined, thinking-first approach to solving complex problems.

“science starts by rejecting the fantasy of infallibility and constructs an information network that acknowledges error as inescapable, fostering continuous improvement and innovation”

— Yuval Noha Harari —

It is time to let empiricism take front and centre. It is time that we start taking empiricism seriously and show the same discipline and pride in our work that scientists show. This starts with embracing the responsibility for critical thinking.

To help us with this new phase, I proposed a new set of Principles to guide our work in a recent article. A set of principles that aim to restore the intellectual backbone of Agile — empiricism as an act of intent, not chance:

Own the Problem and the Solution — when you apply a solution without understanding the problem, you surrender control and become a spectator. The only person who can decide what the solution might be is the person who is closest to the problem — you. Embrace this responsibility.

Be a Learner — effective problem-solving requires knowledge. The only way to take responsibility for this is by continuously learning.

Be Critical — to wield knowledge effectively you need wisdom. Wisdom comes from a deep-seated need to understand the context and the limitations of the knowledge you have. Being critical is the only way to discern what the value and applicability is of any knowledge.

Be Creative — you may stand on the shoulders of geniuses and most of what you create may be derivative, but in the context of your particular problem, the solution will always be an act of creation, something unique.

Be Humble — humility is the foundation of continuous improvement. It leads to the need to experiment and validate, a quest to make absolutely sure your solutions truly work.

Be a Teacher — teaching solidifies understanding, forcing you to articulate your thoughts. This is the true sign of mastery of your profession.

Incidentally, when I wrote that article, I fully expected someone to point out I was simply describing a scientist with these principles. But that didn’t happen. I think that proves my point.

Erik de Bos © 2024