Changing the Way We Learn: From a Factory Mentality to a Growth Mindset

How Critical Thinking and a Thirst for Knowledge Leads to a Life of Meaning and Professional Success

published 05 October 2025

If having a clear and inspiring goal is essential for our intrinsic motivation and the enjoyment of life, as Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi tells us in his book Flow, then for many of us, our lives are a constant challenge to find those goals. In essence, asking questions is perhaps the only way to keep finding our way, at least for those of us unable to accept someone else’s authority on the matter.

Asking questions is what led to the development of the first institutions of knowledge and wisdom. Here in Western Europe, almost 2,500 years later, we are still inspired by the ideal set by Plato’s Academy, a community of knowledge that gathered in a garden to discuss topics ranging from astronomy and mathematics to logic and ethics.

The focus of these institutions was the arts, ethics, music and dialectics and other forms of discussion, with a willingness to present surprising findings and the openness to discuss them without inhibitions.

While back then knowledge was pursued for its own sake, a practical attitude gave focus to a pursuit of oratory: the craft of persuasion. In essence, wise men learned to become leaders, able to inspire and influence others and therefore steer the course of events. We still see a remnant of this approach in what is nowadays referred to as a classical education.

On the opposite side of the social ladder, craftsmen learned their craft from a master who would take them on in an apprenticeship lasting anything from months to years. While the wise men in Plato’s garden also sought a master, attracted by their knowledge, here the master-apprentice relationship was stricter and more hierarchical. But the approach to imparting knowledge was much the same. While working together day by day on their craft, the master would teach his apprentice everything he knew.

Taylor Strikes Again

It is surprising to realise that education remained much the same for thousands of years, only changing into the system we are all familiar with today about two centuries ago, with the advent of the Industrial Revolution.

The huge migration of labour towards factories led to a new social problem: what to do with children while both parents worked? The solution: the development of the modern public school system.

Following familiar Taylorist patterns, schools focused on practical, standardised skills, dictated by the needs of industry. Children were prepared to become the next generation of exchangeable cogs in the machine.

Taylor dedicated himself to the precise measurement of individual worker movements to improve efficiency, and similarly, education was intimately focused on delivering the perfect worker. And of course, a no less important goal, ensuring future workers learned to be obedient and docile.

Learning became mechanical and standardised, with little attention to creativity and communication, because where everything is prepared to ultimate perfection by an elite, only honest work remains and no time for socialising. God forbid new and strange ideas that might render all that perfect preparation useless! Beware the workforce able to think for themselves and aware of the fallacy of a superior elite!

We may laugh at this now, woefully forgetting CVs and cover letters, job descriptions, certificates and diplomas, all of which are tools designed for the same purpose: to make us easily manageable resources.

For the elites, the ones who could previously afford a classical education, life actually became easier. With the workforce excluded from thinking, future managers no longer required persuasion skills to coax the workforce to, well, work. With factories focusing on conveyor belt efficiency and the simplification of workers into resources, managers could instead focus on the mechanics of running an organisation. Literally, the mechanics of the machine. Ironically, trapping themselves in the same mechanical and standardised worldview as the workers.

Incidentally, this is the reason why in most business trainings and education, there is little attention for the more human aspect of the job (McKinsey, HBR). There simply is no need to train leaders, because there is no one to lead.

The Growth Mindset

A fellow Scrum Master asked me once,

“Why do they pay us to do what we do? Isn’t it just plain common sense?“

Indeed. How is it that some people just simply get it? And how is it that there are Scrum Masters with years of experience who are still stuck in a mechanical perspective of Scrum?

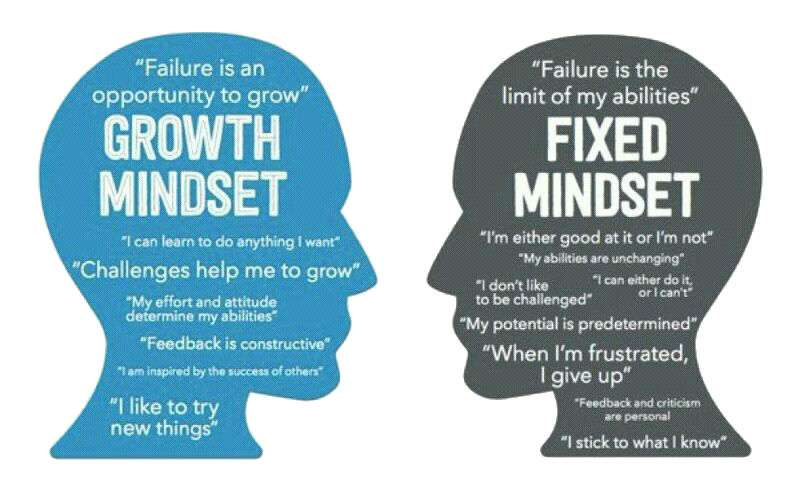

In essence, it has to do with the way we learn. In her book Mindset: The New Psychology of Success, Carol Dweck describes how success, and the ability to learn and adapt, depend on your attitude towards learning: your mindset. At one end of the spectrum is the growth mindset, which is the ability to embrace challenges and view effort as a path to mastery, believing abilities can be developed. In contrast, the fixed mindset avoids challenges, fears failure, and views talents as static, limiting growth.

This idea is pretty easy to transpose to the ways of learning I described above. The Platonic or classical way of learning obviously corresponds to the growth mindset, in which the goal is the joy of learning itself, the surprise and reward of new insight, of new ideas. We pursue knowledge for its own sake, an intrinsic reward.

The Taylorian way corresponds to the fixed mindset, a factory mentality. The goal is not the learning itself, but the rewards that learning provides. A high salary or guaranteed employment, for example. In that sense, learning is a bureaucratic hurdle to prove your worth so you can be admitted to better things. An extrinsic reward.

Let me illustrate.

When I decided to study Ecology at university, my Colombian family (my mum is Colombian) thought, wisely, that I was being stupid and should instead become a doctor or a lawyer. I understood the security of that choice, but, being young and stubborn, I stuck to my choice.

After my studies, I never managed to get a job as an ecologist (proving them right), and eventually became a programmer. My family breathed a sigh of relief when that turned out to be a lucrative career. Only to moan in despair when, after 15 years, at the peak of that career path, I threw it all away to become a Scrum Master.

For most of my life, I’ve lived with a certain gnawing sense of guilt about indulging this irresponsible attitude. It felt selfish, to be purely driven by the pursuit of enjoyment.

The irony is thick: I achieved success in two different careers by being terribly irresponsible and only doing the things I enjoy passionately, while if I had sought security, I would have forced myself to a path of obligation and discipline that I would not have enjoyed and would probably have killed my spirit.

“becoming is better than being”

—Carol Dweck—

Two very important factors are at play here: Flow and Fear.

Flow

As I mentioned above, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi argues that the mental state of flow is the source of our enjoyment of life: the key to a fulfilling life and a sense of serenity.

In his book, he describes how flow results from the freedom to pursue inspiring goals, during which process we develop our skills, allowing us to tackle ever-growing challenges. Indeed, there is a depth to what we are capable of as human beings, something of which we have only touched the surface. Cal Newport, in his book Deep Work, and Steven Kotler in his book The Rise of Superman, both explore this idea, giving us intriguing hints of what may be yet to come. And everything points towards the growth mindset.

Perhaps most important is the connection between enjoyment and effectiveness, the fact that allowing people to enjoy their work, by providing them with inspiring goals and the freedom to pursue them, makes them so much more effective.

After two centuries of hierarchy and autocracy and the appalling effect it has had on our society, the irony is just too delicious.

Fear

In their book The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity, Graeber and Wengrow postulate that there are three factors necessary to resist domination by others:

the freedom to move away when someone tries to force you to do things you don’t want,

the freedom to disobey when someone tries to force you to do things you don’t want,

and the freedom to create or transform social relationships, in other words, the freedom to change the way society is organised.

This may come as a surprise, but in our modern world, the absence of these freedoms is starkly visible. The global migration crisis illustrates how the freedom of movement is an illusion, a luxury reserved for the rich. The mass arrests and violent suppression of movements like the Occupy Movement illustrate how the freedom to disobey is only condescendingly tolerated. And our struggling democracies show how we are less and less able to influence how we organise our societies.

Without these freedoms, consciously or unconsciously, willingly or grudgingly, we live in a society of domination. A society which is essentially ruled by fear. A society ripe for a fixed mindset.

The tragedy of our times is the fact that we have created a society in which the majority of people, all born with innate optimism and dreams, have been so abused by an inhuman bureaucracy and a callous elite, and, lacking freedom to resist, have become hopelessly stuck in a fixed mindset and will never be able to recover a growth mindset. They live in a fortress of cynicism and mistrust, completely unreachable, untouchable.

Indeed, fate is not without a sense of irony, quoting Morpheus in The Matrix: the side-goal of keeping the workforce docile seems to have been so effective that we now struggle to understand why fear and a fixed mindset dominate our societies and why we are only now rediscovering flow and the path to a life of fulfilment.

Conclusion

The implications are huge.

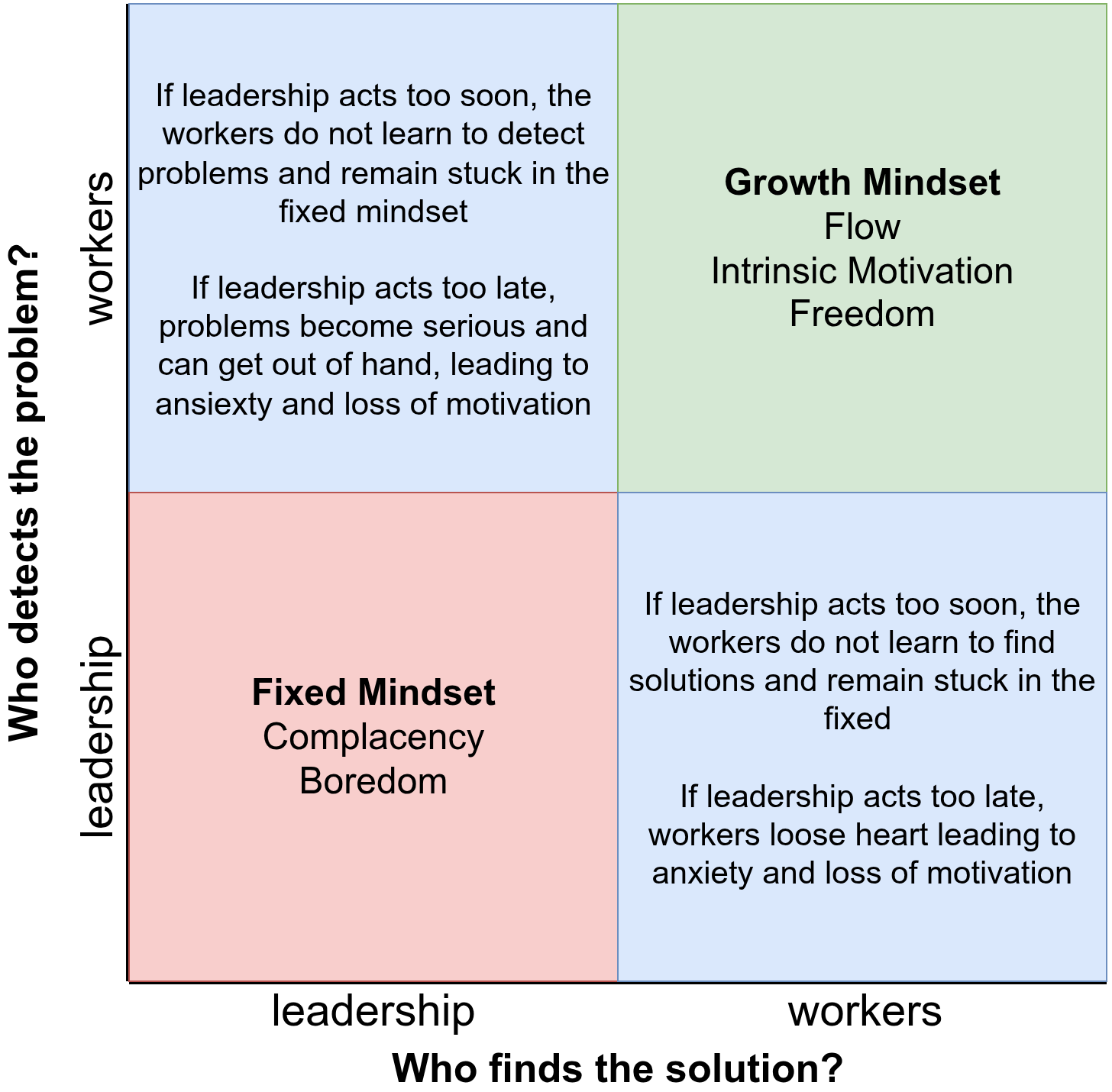

For me as a Scrum Master, bent on improving the effectiveness of the people I work with, it means that my work doesn’t really have anything to do with frameworks and processes, but instead it is about guiding them towards a growth mindset. Subjects like the enjoyment of work and creating flow are valuable tools in this endeavour.

More generally, it makes clear that our struggles with Agile and other new ways of working are all fundamentally geared at freeing us from fear and recovering the growth mindset: critical thinking, the ability to think creatively, the courage to make mistakes, the self-confidence to try out new things, take responsibility and persevere.

It also makes it clear where we Agilists have lost our way. We have let our ideals be absorbed into the factory mindset. We now fit perfectly into the organisational chart and HR defines our career path. Certifications and assessments check the boxes of our knowledge and guarantee that we just as rigidly enforce our rigid skills and frameworks and best practices, a binary mentality that has effectively destroyed our freedom of thought.

How we view the Scrum framework illustrates this. From a fixed mindset perspective, we see Scrum as a set of rules that define a process. While in fact Scrum is fundamentally designed to encourage a growth mindset by developing flow and helping people to deal with the fear of uncertainty. Ironically, this is only apparent when viewed from a growth mindset perspective.

Essentially, our Agile movement is but one small episode in a long struggle for freedom, particularly the freedom to pursue knowledge. What makes our time so special is the fact that we have reached a level of development where complexity dominates our society, making the need for an effective workforce essential for success, and therefore making enjoyment as a catalyst for that effectiveness a competitive advantage. The setting is ripe to enter a new age in which effectiveness goes hand in hand with freedom.

We have come full circle. Our quest for the Learning Organisation, our Chapters and Guilds, all reflections of Plato’s Academy, show our first hesitant steps. Slowly we are realising that mastery is not a destination, but a journey. There is always more to learn. Who is a master? He who is ready to accept the responsibility of training others. Nothing else. Nothing is fixed, nothing is impossible with a growth mindset. Let that sink in, because it is here that we find the true definition of leadership.

The way we learn determines what kind of leader we will become. A leader to uphold the status quo. Or a master of the growth mindset, a leader to inspire us to excel through fulfilling lives.

Erik de Bos © 2024